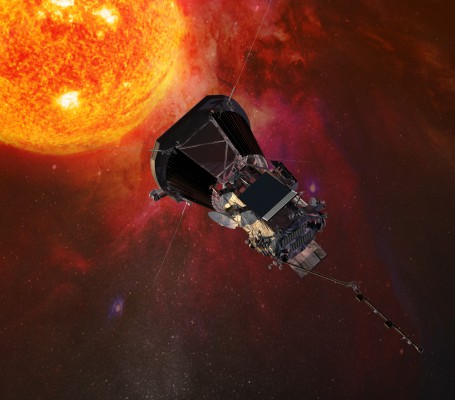

When a NASA probe launching in mid-2018 approaches its final destination – the roiling upper atmosphere of the Sun – the spacecraft’s heat shield will encounter temperatures hot enough to melt steel.

Testing conducted by Southern Research engineers demonstrated that the carbon composite materials selected for the Solar Probe Plus’ thermal protection system will protect the craft and its instruments from the relentlessly brutal conditions.

“The probe is going to be getting pretty hot, pretty toasty, and it’s going to be hot for a while,” said Jacques Cuneo, a member of Southern Research’s

engineering team who worked on the project. “It’s not a transitory thing; it’s going to be baking for a while.”

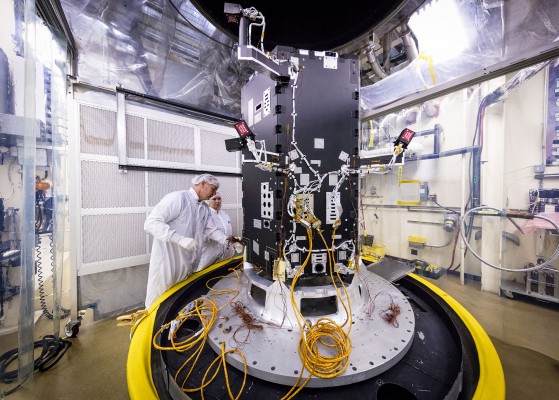

The Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland is managing the mission and building the spacecraft. The lab brought in the Southern Research team to conduct high-temperature evaluations of the heat shield materials – a task the Birmingham non-profit organization has been performing since the early days of NASA.

Making sure the Solar Probe Plus can handle the hazards of intense heat and radiation is crucial. Scientists have imagined a mission to the Sun since 1958, and data collected by this probe will yield important new insights about the sun’s atmosphere – known as the corona – and its role in producing fierce solar winds.

Scientists want a deeper understanding of solar activity so they are better able to predict space-weather events that can impact life on Earth and disrupt the operations of orbiting satellites.

“The talented engineers and technicians at Southern Research have made many important contributions to the nation’s space program over several decades,” said Michael D. Jones, vice president of Engineering. “Solar Probe Plus is an exciting mission, and we are proud to have been part of an endeavor that will advance scientific knowledge about the Sun.”

REVOLUTIONARY MISSION

The Solar Probe Plus will travel closer to the Sun than any previous spacecraft, approaching as close as 3.9 million miles as it hurtles past the star at 450,000 miles per hour. That will put the craft well within the orbit of Mercury, the planet nearest to the sun.

Over seven years, the probe will complete two dozen solar orbits, using seven gravity-assisted flybys of Venus to skirt continually closer to the Sun’s blazing corona.

So it can perform this revolutionary investigation, the spacecraft and its instruments will be protected from the heat by a 4.5-inch-thick carbon composite shield capable of withstanding temperatures climbing to more than 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit, according to the Applied Physics Laboratory.

“As you can imagine, the heat shield is a big article,” Cuneo said. “It’s made up of carbon-carbon sheets on the top and the bottom, and in the middle, there’s a rigid carbon foam.”

The Southern Research engineering team was asked to determine the mechanical and thermal properties of the heat shield materials. The carbon composite used in the sheets represented familiar ground for testing, thanks to Southern Research’s longstanding involvement in the space program.

The carbon foam, however, was different. Just figuring out how to the test the relatively brittle open-cell foam was technically challenging, Cuneo said. The issue: How can you measure strain when you can’t even touch the specimen?

“When you pressed on the foam, it would create dust. It wouldn’t actually break, it just kind of machined itself down,” Cuneo said. “Anything that generated compression was a real issue with the foam, so we developed a way to stiffen the ends by impregnating them.

“We were able to figure out how to grab and pull or torque a specimen, and develop ways to measure strain because you couldn’t mount anything on the specimens,” he added.

The Southern Research engineers generated a database of the carbon foam properties, and the material passed muster.

“The foam fit what they thought it was going to do – particularly at high temperatures, which is what they were concerned about — and it’s on track for launch,” Cuneo said.

In July 2016, NASA said the Solar Probe Plus is slated to launch during a 20-day window that opens on July 31, 2018. The spacecraft has passed NASA’s design review stage, meaning it is has moved to final assembly. Engineers at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory are now finishing assembly and installing spacecraft systems and science instruments.