Southern Research scientists are targeting a specific protein complex in influenza in the search for a new drug to counter a virus that infects more than 3 million people each year and has a history of catastrophic pandemics.

“Influenza remains a big killer,” said Mohammad F. Saeed, Ph.D., a research scientist in Drug Discovery who is directing Southern Research’s program to develop a treatment against the virus.

Influenza is blamed in the deaths of between 250,000 and 500,000 people across the globe each year, according to the World Health Organization. In the U.S., annual flu deaths range from around 3,000 to just under 50,000, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates.

Vaccines offer protection against seasonal influenza, but Saeed says there are many reasons to pursue the development of a broad-spectrum antiviral that’s effective against several strains of the virus. That’s the goal of his work, which is funded through a National Institutes of Health grant.

“Let’s say we have a pandemic like we had in 2009 with swine flu — the vaccine wouldn’t work against that because that is a different variety of influenza,” Saeed said. “Every now and then, you see a different strain of influenza entering human population and becoming more prevalent globally because the existing vaccines are ineffective against the new strain. To generate a vaccine for the new variety, it would take six to nine months, or a year.”

Scientists say the 2009 swine flu was a new form of the H1N1 influenza virus that rapidly spread around the globe much like the 1918 pandemic that killed as many as 100 million people, most of them young, healthy adults. The CDC put the death toll from the 2009 swine flu pandemic at 284,000 worldwide.

BIRD FLU DANGERS

In addition, the threat posed by avian influenza underscores the need to develop an effective antiviral treatment as a protective measure, Saeed said.

While bird flu doesn’t typically infect humans, there are no vaccines for these influenza strains. Plus, the H5N1 avian influenza virus has shown a very high mortality rate in cases of human transmission.

“Normally these viruses don’t jump species, from birds to humans, but our biggest concern is what if they acquire mutations in nature so that they can more frequently infect humans?” Saeed said. “That would become a big problem, because these viruses are more pathogenic than the influenza virus we see in human populations.”

With no vaccine available, a highly pathogenic mutated avian influenza virus would likely kill people in greater numbers, and even those otherwise healthy individuals who usually can fight off infection with the seasonal influenza viruses.

“That’s our concern, and that’s why we want to have drugs against influenza viruses,” Saeed said. “In an outbreak, if we don’t have time to get a vaccine in place, we’ll at least have drugs for people who are already infected to save their lives.”

TARGET: POLYMERASE

Researchers have developed drugs that are useful against influenza, but the virus can develop resistance.

For example, amantadine, which disrupts the virus release from infected cells in Type A influenza, and thereby prevents its spread, is no longer recommended for treatment of influenza in the U.S. because of resistance, Saeed said. The CDC says sporadic resistance has been spotted with oseltamivir, the most widely used antiviral flu medication.

“These viruses mutate all the time. That’s the way they work,” Saeed said. “For us, the important point is to target some protein in the virus that doesn’t mutate as frequently.”

The Southern Research team is targeting a protein complex in influenza viruses called polymerase, which plays a central role in viral replication. In recent years, scientists have made breakthroughs in revealing the structure of this protein complex, opening opportunities for sophisticated drug design techniques.

Additionally, the polymerase protein complex is relatively consistent across several influenza virus subtypes, meaning a drug that works against one form of the flu could work against many others.

“Without those proteins, the virus cannot replicate,” Saeed said. “If we can inhibit those proteins, we can stop the virus in its tracks.”

Scientists also believe that because this set of three proteins performs such an essential function to the virus, mutations within the complex should be rare. That means the likelihood of the virus developing resistance to a polymerase-targeted drug should be low.

DRUG DISCOVERY

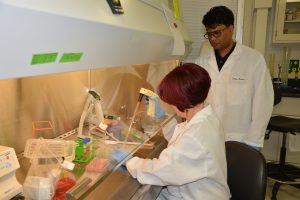

Southern Research, whose antiviral work started in the 1950s, is well positioned to make advances against influenza.

Scientists at the organization’s infectious disease labs in Birmingham and Frederick, Maryland, have studied a wide range of viral threats, from polio and HIV/AIDS to dengue and Zika. It has a vast library of compounds to examine for activity against influenza, and a state-of-the-art high throughput screening facility with dedicated experts to perform that operation at scale.

“We have a compound collect with approximately 500,000 samples available for screening against influenza viruses,” Saeed said. “We start with the seasonal and pandemic strains. Then we’ll test the compounds that show activity against the avian viruses.”

So far, the Southern Research team has tested about 200,000 compounds in the collection, turning up close to 900 “hits,” or agents that showed activity against influenza, Saeed said. Further screening determines whether the agents are acting against the targeted protein complex.

As part of the drug discovery process, Southern Research chemists assist by designing new molecules from the active agents that are better tolerated in the human body and consistently reach the target area in the virus.

“There are multiple subtypes of influenza viruses, so our goal in this program is to find small-molecule drugs that could potentially have activity against many different subtypes,” Saeed said.

“Influenza pandemics have killed millions of people, and in the case of an outbreak of a highly pathogenic influenza virus, there just won’t be time to develop a vaccine,” he added. “We need a drug against this threat.”