Ruby James was a chemistry major at Birmingham-Southern College when she got her first glimpse of the laboratories at Southern Research Institute. The tour opened her eyes to the power of applied chemistry.

“I was extremely impressed, and it encouraged me to want to know more and to be a part of the institute,” James later recalled.

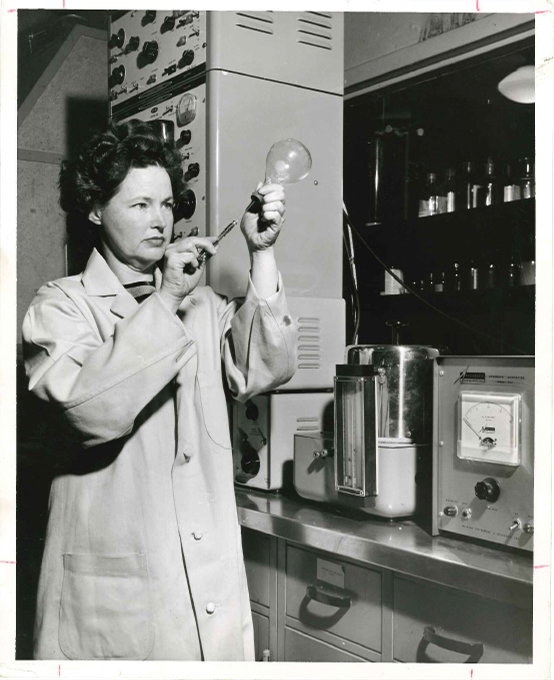

When she joined Southern Research in the early 1950s, the labs, manned by a half-dozen chemists, were in the Morris-Cartwright House that served as the institute’s headquarters. Four decades later, James retired as head of the analytical chemistry department at Southern Research, her instinct about applied chemistry completely validated.

“It was probably the most exciting thing in my life to come and work for the institute, and that was 40 years ago,” she said in 1991. “I still feel that excitement about the institute.”

To mark Women’s History Month, Southern Research is remembering some of the female scientists who helped the Birmingham-based organization make discoveries that led to safer space flight, effective cancer treatments and many other advances over its 75 years.

“Ruby James was a trailblazer at Southern Research whose work in our chemical labs earned her respect in a traditionally male-dominated field,” said Art Tipton, Ph.D., president and CEO. “Her long-lasting contributions, along with those of our other women scientists, helped to position the institute as a premier research organization with international recognition.”

She joined Southern Research at a time when there were few jobs for female chemists in Birmingham, and most industrial chemistry labs didn’t even have a women’s restroom.

FUMING ACID

James’ first project at Southern Research involved working with red fuming nitric acid – a corrosive, combustible concoction used for rocket propulsion. The team was attempting to measure water in the acid because too much moisture would render it useless as an oxidizer for rocket fuel.

The acid “was as bad as anything you could possibly work with,” she admitted.

At one point, after the supplier quit manufacturing the fuming acid, James had to distill it herself at the Southern Research labs because the supplier quit manufacturing it. One chilly day, she had to open the windows in the lab to get the conditions right for producing the acid – an innovative move not appreciated by shivering co-workers.

“Sometimes you do things scientifically that do not appear to the casual observer to be so,” she recalled.

In the 1960s, James became involved in the space race. Southern Research won a contract to staff an engineering materials lab at Kennedy Space Center during the Apollo program. The lab provided technical support to the contractors helping NASA to launch giant Saturn rockets.

By this time, she had become Southern Research’s specialist in gas chromatography, a means to separate the different components of a mixture by forcing gas through a column.

“Since it was a new technique, they did not have anyone trained in that area, and so they asked me to go – and I was happy to go,” James recalled in 1991. “I bought a house, moved my family, and lived in Florida for two years.”

FAR-SIGHTED RESEARCH

Soon after her retirement at Southern Research, James looked back at the cutting-edge work performed in Birmingham, much of the investigation far ahead of its time.

Beginning in the 1950s, this included looking at the health and safety of food products, water toxicity, hazardous waste, and air pollution, along with many other topics that grew in importance over time, she recalled. In addition, there were key contributions to the nation’s space program, starting in the early days.

For James, the groundbreaking work showed just “how important it was for a research organization to be formed here when it was formed.”